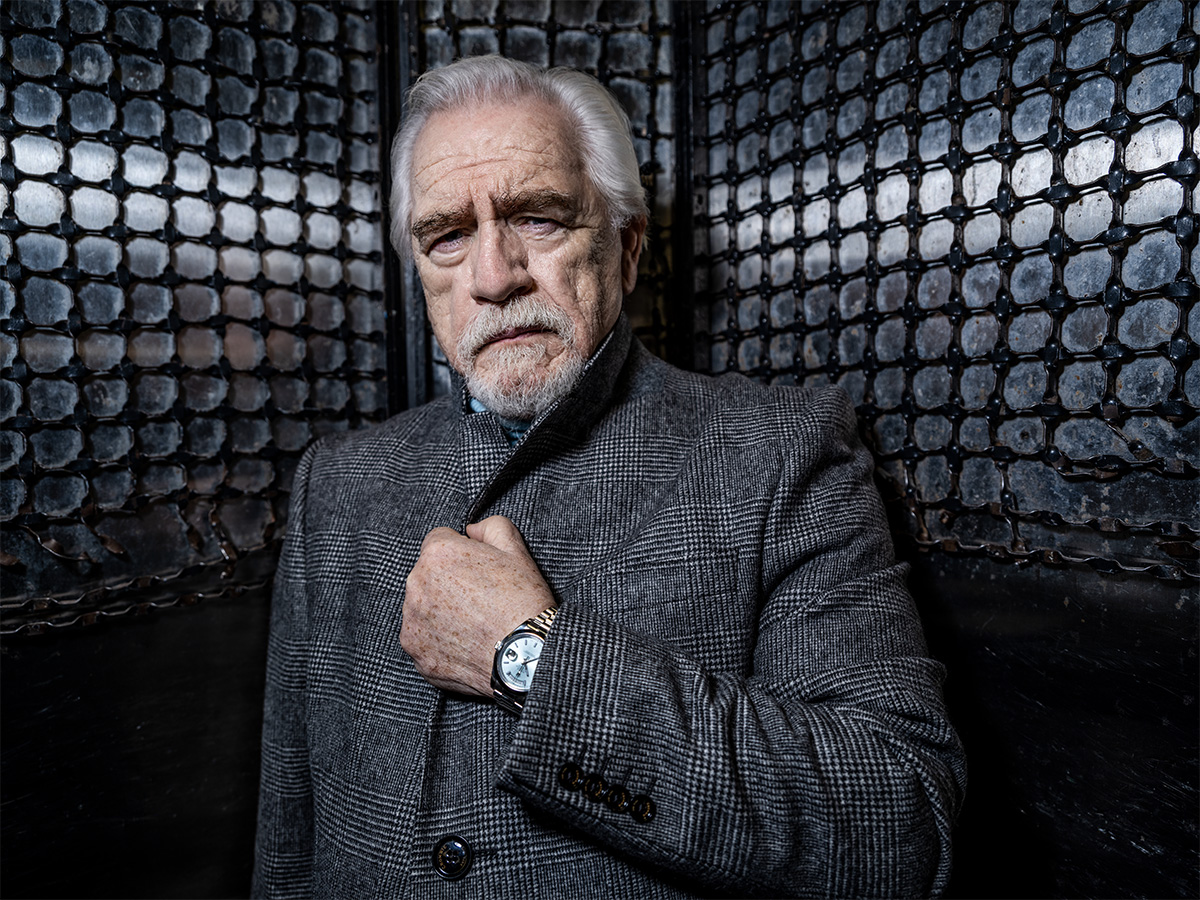

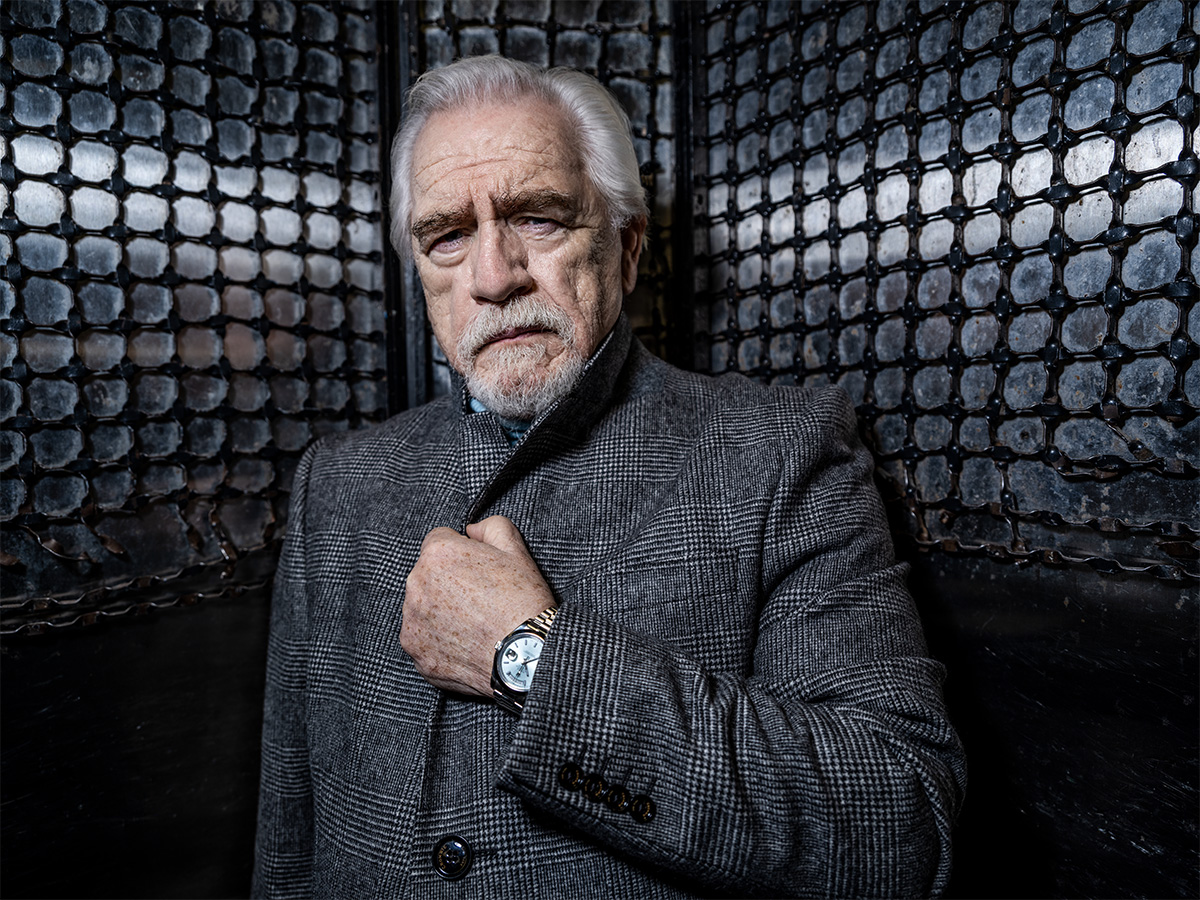

It’s The Beginning Of The End For Logan Roy — Brian Cox On His Final Journey & The Watches He Wore

BRIAN COX IS EXPLORING BOTH SIDES OF THE WEALTH GAP FROM A PRIME POSITION AS SUCCESSION’S RUTHLESS PATRIARCH, LOGAN ROY.

BY LAURA SCHREFFLER

PHOTOGRAPHY SCOTT MCDERMOTT

STYLING VENK MODUR & MICKEY ABBATE

GROOMING LISA-RAQUEL

SHOT ON LOCATION AT THE NED NOMAD, NYC

When Brian Cox, CBE (that’s Brian Cox, commander of the Order of the British Empire, to you), discovers that his Haute Living photo shoot is taking place at The Ned NoMad, the veteran star of stage and screen has to chuckle. In New York, The Ned is a glamorous hotel and members’ club. But actually being a “Ned”? Let’s just say the term has a vastly different meaning in Cox’s native Scotland.

“A Ned is a clever dick, really,” the 76-year-old thespian explains over Zoom from the Brooklyn brownstone he bought last May. He is still laughing to himself as he turns off his TV — he had just been watching a classic film, as he’s wont to do; this time, it was the 1938 Gary Cooper/Claudette Colbert romantic comedy, Bluebeard’s Eighth Wife. “It’s a particularly Scottish thing,” Cox continues. “He’s a smartass. He thinks he knows it all, but he actually knows nothing.”

I wonder aloud whether Logan Roy, the steely, ruthless media magnate Cox plays (and won a Golden Globe for his portrayal of) on HBO’s hit series Succession, would be a Ned, but I’m conflicted even asking it. The Roy family patriarch is many things, but he actually does seem to know it all. After all, in the show’s season three finale, Logan had completely turned the tables on his family of backstabbing children — Kendall (Jeremy Strong); Siobhan, appropriately nicknamed “Shiv” (Sarah Snook); Connor (Alan Ruck); and Roman (Kieran Culkin) — neatly and effectively preventing them from staging a coup to overthrow him as the head of family conglomerate Waystar Royco after learning of his plan to sell the company.

This, to me, seems like a man who makes it his business to know it all. And I would be right.

“Logan is beyond a Ned,” Cox explains. “He might have been a Ned for about five weeks in his younger years, but he’s beyond that now. Now, Logan is a law unto himself.”

You could also call him a freaking legend. Evidently, he is not the kind of man that goes gentle into that good night. “I have you beat, you morons,” Logan harumphs to four of his children as he stomps out the door in that final episode. Which means that when the fourth season premieres on March 26, the Roy family had already effectively imploded. But who is going to pick up the pieces? And where does Logan go from here? Surrounded by a sea of sharks — though he may have the sharpest teeth — he is alone.

In Cox’s opinion, Logan isn’t a villain (or a Ned anymore). He’s not a monster — he’s just a man, albeit one who gets shit done … like preventing his entitled, good-for-nothing offspring from ruining the company he built from scratch, for example.

“Logan’s not that bad. I actually have a lot of sympathy for Logan,” he admits, recounting a particular scene he had shot earlier that week. “[Logan] comes out onto the street, and he just sees how run-down New York is. There are rats everywhere and a guy eating his supper out of a tin can. Logan sees that and goes, How did this happen? How did we get to this state? It’s a parallel to his own life: he has these awful, entitled children, but he himself does not have that entitlement; he has empathy that his children do not. He believes that everything he’s done, he’s earned … and he’s not wrong.”

Cox continues. “It’s always said that a cynic is a disillusioned romantic. I think that’s true and also the root of who Logan was as a young man. He sees that life doesn’t operate the way one would like it to, but in a more mercenary way. His children, however, don’t realize that if they don’t work, that if they don’t commit some kind of integrity to what they do, that they can’t succeed, and he can’t do anything about that. It’s just the nature of the beast.”

As is the fact that, due to a seriously strict NDA, there isn’t much Cox can reveal about the upcoming season. I expected that any excavating expedition wouldn’t unearth much. But the scene he sets, however brief, is still an insight into how bleak Logan’s world has become: his disillusionment, his disappointment, and perhaps even his regret.

Because although, like his children, Logan Roy is power-hungry, he has changed. And Cox, who has worn this character like a second skin for the past three seasons, is the best equipped to speak to those changes. His opinion of Logan’s current place in the world? That would be “stuck.”

“I think that’s his tragedy, in a way. There’s a certain misanthropy there, and we haven’t been given clues as to where that misanthropy comes from,” he maintains. “That’s why the writers are so gifted, because they don’t dwell on that. They know that human nature is much more complicated. And so Logan is full of little clues, but there’s not a resolution to him because the writers don’t want that resolution.”

So where does he go from here, this life unfinished? Is there up, or only further down? “It will progress, and it does progress; life progresses, and that will happen,” Cox says vaguely, his lilting, lyrical accent softening the blow of his ambiguity.

He does say this, though: “It’s going to be jolly exciting. Our writers have vision, and we have to trust that vision. They don’t want to give any of it away, and I understand that. When something is as good as what we’ve created, it becomes relatively precious. It’s fascinating to be in the middle of it and observe how people react to it. It’s an important show, because in a sense, [creator Jesse Armstrong and his team] are really political writers. They are really examining human nature and what it does to our day-to-day existence.”

It’s long been thought that Succession was inspired by the life of media magnate Rupert Murdoch. But is there truth to it? According to Cox … maybe.

“Everybody says that, but I just don’t know,” he admits. “Logan thinks people are pretty awful — he’s got a bit of a negative view of life. I’m not sure if Murdoch’s like that. But because there are three boys and a girl in the family, everyone naturally assumes it’s the Murdochs. And the Murdochs might have been a spring-off board, but it’s a very different family.”

Since Cox is not the writer, it’s probably a good thing he can’t definitively say if the News Corp founder’s family was the impetus for Succession … especially given that he had an accidental run-in with one of them.

Just before the third season premiered, he was hanging out, having a latte at a local café in Primrose Hill — the upscale London neighborhood that he calls home when he’s not in New York — and someone behind him in line opened a conversation with, “You know, it’s interesting.” Cox continues. “I said, ‘What?’ He went, ‘The show, it’s really interesting. We’ve really taken to it.’ I said, ‘Oh, that’s nice.’ But then he added, ‘Well, my wife has a little difficulty with it now and again, but on the whole, she’s actually pretty tolerant of it.’” In the retelling, Cox raises his eyebrow, saying sardonically, “I said, ‘Well, I’m very glad your wife is tolerant of it. And who might your wife be?’ [Drumroll please.] He said, ‘My wife is Elisabeth Murdoch.’ I went, ‘Oh! Well! You know, it’s not about the Murdochs. It’s just coincidental.’ He said, ‘Oh yes, they know that. They know their own family history, so they know [Succession] is very different, and in their opinion, they don’t behave like that. In their opinion; I don’t venture into that territory.’”

Of Murdoch’s husband, artist and art dealer Keith Tyson, Cox recalls, “He was very sweet, actually. He said, ‘Do you think you could maybe be a little kinder to her in the next season?’ I had to tell him, ‘That’s not what this show is about.’ Their opinion is their opinion. This show is not the Murdochs. It’s the Roys. And Logan is a very different animal from Rupert. They probably have a cynical outlook about what things are, but apart from that, there’s a difference.”

So now you have the answer to one question at least, but there are so many others … and sadly, fans of the show will just have to wait for new episodes to get answers for the rest, except one big one: the series’ fate. Sadly, this season will be Succession’s last. According to an interview with Armstrong published by The New Yorker in late February, Succession will indeed conclude at the end of season four.

Not that Cox knew it. The cast is essentially kept in the dark (lest they break that airtight NDA).

“It’s hard to say [how long we’ll go on] because there’s so many open questions,” Cox admitted during our January chat. “I truly wouldn’t know. It might go on for another season, it might go on for another two seasons. I will say this: it will only go on as long as its life is valid, and then it will come to its conclusion. That could be one season off, or two. Who knows?” Well, now we do.

As for the other questions, maybe Cox is more like Logan Roy than I thought. Both are very good at holding their cards close to their chests when everything is on the line.

T SEEMS THAT THE LIFE OF LOGAN ROY is the polar opposite (and yet, also a parallel) to some real-life folks featured in Cox’s recent passion project, the two-part documentary How the Other Half Live (which could also be called I Am Nothing Like Logan Roy … or, you know, something along those lines). It hasn’t been released in the U.S. yet — only in his native U.K. — but he’s hopeful.

Given that Succession is very much about how money can tear the rich apart, Cox wanted to explore the other side of that and how extreme destitution could do the same. “It was very important to me to do that which is corollary to Logan and what Logan represents, because Logan is all about money. I realized I had to do something.”

When producer Tom O’Brien came to him with an idea about doing something focused on money, he leaped at it. “I went, That’s it! Everything just fell into place. And I’m very proud I did it, because nobody else dared to do something like this. Everybody talks about everything — they’ll talk endlessly about religion or what have you — but nobody ever talks about the religion of money. Which is a religion, just not one that people will admit to you, you know?” he says.

Cox’s deep dive into the wealth gap had him personally interviewing folks in low-income areas, searching for disparities … and then, clearly, finding them. The project was an exploration for him because he himself grew up in poverty: he is from a working-class Catholic family in Dundee, Scotland, and the youngest of five children. His mother was a spinner who worked in the jute mills; his father, a police officer-turned-shopkeeper who passed away when Cox was just 8 years old.

Like Logan, Cox truly is self-made. He left school at age 15 and headed to England to train at the London Academy of Music & Dramatic Art at age 17. Now, at age 76, he is one of the most respected actors in Hollywood, an even sweeter achievement because he got there all on his own.

As we continue discussing his past and present, there’s a lot of leapfrogging. Somehow, we even end up talking about Prince Harry and Meghan, Duchess of Sussex (as you would when sitting down with a Briton and winner of a Primetime Emmy and two Olivier Awards). But you’ll have to wait a little for the monarchy part of our chat.

He tells me his true tales: his family history, the grandfather he never met, how British history shaped his family, and the recent revelations he had after appearing on PBS’ Finding Your Roots earlier this year. We talk about human rights, and he gives me history lessons. (I have officially been schooled by Professor Cox, whose lessons included everything from George V to Queen Victoria to World War I. But seriously, he really is a teacher, many times over. He has an honorary doctorate in laws honoris causa conferred by the University of Dundee in 1993; an honorary doctorate of drama conferred by the Royal Conservatoire of Scotland in 2006; an honorary doctorate of letters bestowed by Queen Margaret University in Edinburgh in 2007; an honorary doctorate of drama presented by Edinburgh Napier University in 2008; and an honorary doctorate of letters conferred by southwest London’s Kingston University in 2011. He was also elected as the 12th rector of the University of Dundee by its students in 2010 and re-elected in 2013. So, there you have it.)

He even touches on his views on God (or lack thereof). “I think one of the most fundamental problems we have as humans is that we let religion get in the way so much of the time,” he announces. “I’m not anymore, but I was born a Catholic. I’m pretty much an atheist now, because I don’t think religion serves anybody. I think God is one of the great illusions we cling to in order to give us sanity, but I actually believe in human beings, that they’re much more interesting.”

“That is why I love the theater,” he declares. “For me, the theater is the one true church because it’s where you see human beings attached to all those things deceptive to them, all those fantasies. I think religions are fantasies. But it’s fine. Whatever gets you through the day, I say don’t knock it.”

If you’re talking about knocking Donald Trump, though, all bets are off — he hammers America’s former president mercilessly and unabashedly during our talk. I mention his tirade on Trump for a reason (and not just because he calls him a “self-serving, horrendous shite” — a phrase I find hilarious). It’s because it leads into the reason Cox and his wife, Nicole Ansari, have made the States their primary home.

“The reason why I live in America, and why I love it, was that I was very attracted by the notion of egalitarian thinking. This country was built on essentially egalitarian principles. And I feel horrible for the immigrant population that comes here with this notion that America represents freedom, because it’s certainly not as free as it purports to be. We’ve allowed so many things to get in the way of that freedom. For me, one of the tragedies of America — because I do love this country and what it represents — is that it isn’t living up to what it represents. It’s not living up to what those principles were built on because all these other distractions have come in.”

But hope springs eternal for this born and bred Scot. “It ain’t living up to its potential at the moment, but it will!” he proclaims. “I think it will because I’m an optimist. And that is how I’m different from Logan Roy. Logan is not an optimist. He’s been subsumed by life. I’m still optimistic because I believe that we’re on a journey, that we’re like babes in the woods still, that we’re at a stage of our evolution where we haven’t quite come into the light, or that we’ve seen the light but run away from it.”

And this, my friends, leads us to Cox’s analysis of the British monarchy situation.

Cox pauses. “I find that it’s really just so sad that we don’t acknowledge our own humanity enough. We don’t acknowledge what we’ve been through on behalf of a family — a ruling family. And that’s why, when you look at what’s happening with Meghan and Harry [there they are!], you go, ‘Well, Harry, there’s an innocence about.’ And with her, too. But you can’t go into a system where somebody’s already been trained to behave in a certain kind of way and then just expect them to cut themselves off. I mean, she knew what she was getting into, and there’s an ambition there clearly as well — the childhood dreams of marrying Prince Charming and all that shit we see as fantasy that could be our lives in our dreams. I’m a Cinderella person, you know.” He shrugs. “In my opinion, we shouldn’t have a monarchy. It’s not viable; it doesn’t make any sense. It’s tradition and all that, they say. I say, ‘Fuck it! Move on!’”

It’s hard, I say. Some people feed off the pain of others. It makes them feel happier and better about themselves, as sad and counterintuitive as that is.

He agrees. “That’s why Succession is so popular — people love to hate. They love to look at the Roys and go, ‘Oh, aren’t they horrible.’ They don’t make the connection: you’re not too far away from these people. You know that, don’t you? Given certain circumstances, you’d be in exactly the same situation. You would still be messed up. They love to see them come a cropper. [For those unfamiliar with this phrase, it means “to fail” or “to fall into ruin.”] It’s gladiatorial. ‘Oh, look at these horrible people destroying each other. Isn’t it fun!’ That’s all part of the storytelling of our existence, and it’s true, it’s accurate; it’s not something that’s made up. We’ve forgotten who we are as human beings and who we are in terms of our own evolution.”

Yet, for all the world’s problems — monarchy, patriarchy, Trump — to Cox, it is still a glorious place, especially when he can escape it so frequently by stepping into someone else’s shoes. “This is exactly why I act,” he says, noting, “You know, Hamlet’s advice to the players is the truth of it all. It’s ‘speak the speech, I pray you, as I pronounced it to you.’ It’s about holding the mirror up to nature to show action its own form, and that’s what we talk about. That’s why I like my job — because this is what we do on a daily basis. We hold the mirror up to nature; we present the human struggle. It’s the greatest thing to be able to do. But at the same time, we’ve got to get better at it.”

It’s a lesson, I say. Kind of like, don’t be a Roy.

“Yes,” he agrees. “That’s a true lesson. Don’t be a Roy. Be everything else. Be anything else.”

Although from where I’m sitting (be it just on the other side of his computer screen), being the guy that plays a Roy? I’m not going to lie — that seems pretty damn great.

EVEN WITHOUT BEING ABLE TO TOUR HIS new-ish home, I can tell that Brian Cox is a pack rat. His Brooklyn office houses a slew of treasures in what he intermittently refers to as his “emporium.” I spy a stuffed swan, a bowling pin, a novelty Laurel & Hardy statue with a missing hand.

“I won’t show you my room,” he says before he does just that. “It’s like an emporium. It’s getting worse and worse. I don’t throw anything away.

I’ve got so much crap in here, but I love it.”

What he loves the most — that which stays in his office only when he himself is there and travels with him wherever he goes — is a photograph of himself as a young boy. “The thing that I’ve taught for years — what I always teach my students — is to carry a photo of yourself as a little girl or little boy, because that’s who you are. You’ve gotten old, you’ve grown up, you’ve gotten gray. You’ve gotten fat, you’ve gotten thin, you’ve become beautiful, you’ve become ugly, but that’s who you are.”

To prove his point, he holds the photo up to the screen. It is, as promised, Cox as a baby. “Look at that little boy,” he urges. “Just look at me. That’s me! That wonder of life, I’ve never lost it.”

I am looking; he is seen. But the truth of the matter is, what I think bears no weight. He knows that he has an ability to learn something about himself, to become something more, with each and every role that he takes on. And his resume is extensive: he played the very first Hannibal Lecter in Manhunter (1986); starred in Rob Roy (1995); and acted in Mel Gibson’s Academy Award-winning Braveheart (1995); The Long Kiss Goodnight (1996); The Boxer (1997); Rushmore (1998); L.I.E. (2001); The Bourne Identity (2002); The Ring (2002); Adaptation. (2002); X2: X-Men United (2003); Troy (2004); The Bourne Supremacy (2004); Zodiac (2007); Fantastic Mr. Fox (2009); Red (2010); Rise of the Planet of the Apes (2011); Churchill (2017); and, of course, Succession. He also had a long and impactful stint as King Lear for London’s Royal National Theatre and has written three books. (And while this isn’t exactly an Oscar-worthy project, few know that it has been Cox’s voice gruffly grumbling the McDonald’s jingle for the past few years.)

He says now, “[As an actor], you’re learning all the time. That’s why I love my job — everything you do is a revelation. You are always in a relative state of innocence. You get to be a blank piece of paper.”

Cox is feeling that more than ever with his latest endeavor: his directorial film debut. Glenrothan: Sons of the Whiskey explores his passion for Scotch whisky while simultaneously paying homage to his home country. As created by Scottish actor and writer David Ashton, the project — currently in development — revolves around two estranged brothers of a famous distillery family from the Scottish Highlands who reunite after four decades apart by necessity. In addition to directing the film, Cox will also star as the elder brother, Sandy. At the time of our interview, the role of the younger brother had yet to be cast.

Here’s the plot: the younger brother has a true gift, and that gift is the art of making whiskey. In fact, he is the youngest master distiller in Glenrothan’s history. But a blowout fight with his father forces him to flee to America, where he becomes a prolific music writer, focusing on the blues. Sandy, according to Cox, is the organized brother, the plotter, the one who knows the ins and outs of the small, successful distillery that creates small-batch, high-end, “special occasion” whiskey. But Sandy doesn’t have his younger brother’s talent for producing it. When the screenplay courtesy of award-winning writer Jeff Murphy (Hinterland) begins, Sandy is fed up and ready for a change. “He’s getting on,” Cox explains. “He’s thinking about what’s going to happen to the family business now. He’s not 100% well, and so he sends a letter to his younger brother, who resists returning.” But when he does eventually head back to Caledonia, “everything begins to go both right and also wrong,” Cox summarizes.

For Cox, this project was only right. Thomas Wolfe famously wrote, “You can’t go home again” — but in Cox’s case at least, he was wrong. The actor may have left at 17, but his dreams were born in Scotland, and he will never forget that. “This is a love letter to Scotland — it’s a love letter to the land — but it’s also about understanding the nature of your roots and how your roots liberate you, not bind you,” he explains. And although he plays the older brother, there is something of the younger in him, too. “That he lives somewhere else doesn’t invalidate that fact that his roots are important to him, and not just important, but a fundamental part of who he is. You also have to take into account that even though he moved away, those roots are still there, and those roots gave him the freedom to move away to go somewhere else.”

In a sense, delving into his own history seems to be a motivation for being part of the project, but this movie also gave him the opportunity to reunite with Ashton, whom he last worked with on the British radio crime drama series McLevy in 1999. But at 76, as a man who’s constantly learning and constantly testing himself, trying something new — aka directing — was a welcome challenge. That he has an entire cupboard full of whiskeys back in the U.K., a collection that has grown substantially over the past 40 years, well, that just sweetened the pot. It’s a tough job being Brian Cox, but someone’s got to do it, eh?

As we prepare to bid each other farewell, I inevitably ask for a parting Scottish phrase. We did, after all, start our chat with the etymology of a Ned.

He thinks for a brief moment, and shares this: “My mother used to say that what’s for you will not go by you. It’s destiny. It’s one of those pearls of wisdom that I took for granted, but it’s absolutely true, because if it’s for you, it will happen. If it’s not for you, it won’t happen. If people understood that, there would be a lot less misery in the world.”

SIGN UP

SIGN UP