Novak Djokovic: The Tennis Ace Lives to Serve

Novak Djokovic was gracious in defeat at the press conference following his five-set loss to Andy Murray in the 2012 U.S. Open men’s single final. He didn’t even protest as it became clear that Djokovic would be answering as many questions about Murray as himself. That this even-keeled dignity came from a tennis player who’d become very unaccustomed to losing made it even more impressive.

That September 10 final at Arthur Ashe stadium redefined the top of the men’s game, solidifying the quartet of consistently dominant players — Djokovic, Murray, Rafael Nadal and Roger Federer—that routinely fill out today’s Grand Slam semis and finals. The big four each won a Slam this year, the first time since 2003 that there hasn’t been a repeat winner. Djokovic didn’t duplicate his three-peat of 2011, but he never really expected to. “Obviously, I was aware that it would be very hard to repeat the same result, but that didn’t discourage me from dreaming big,” Djokovic told us in an e-mail. “I’m aware that our best changes from season to season.” Few would know that better than Djokovic, 25, whose career path has been one of propulsive improvement.

Djokovic first raised American tennis fans’ eyebrows at the 2005 U.S. Open during a second round victory against the Croatian Mario Ancic. Djokovic, 18, was the youngest player ranked in the top 100. The Serbian had already caused a stir with his defeat of Gael Monfils, partly thanks to his youth but also because of breathing problems that had incongruously plagued, and nearly felled, the fit teenage upstart.

But the Ancic match came weighted with fraught symbolism—players from opposing sides of the Balkan tinderbox rehashing, in Queens, the bloody conflict that marked Djokovic’s childhood and made for one of the more improbable rises to the top of a sport still tethered in the popular imagination to sedate country club privilege.

Djokovic shrugged off any presumed or metaphorical ethnic animus at the time, but his history is inseparable from that of his fractured homeland. He took to the courts at five-yearsold— his father, Srdjan, owned a pizzeria near a new, modest tennis club in Kopaonik—and was immediately hailed as a prodigy by instructor Jelena Genčić. Genčić had found her own success in Serbian tennis and gone on to coach Goran Ivanisevic and the great Monica Seles. She told Djokovic’s parents he was a “golden child.” At seven years old the phenom went on Serbian television and declared his intention to be the number one ranked player in the world.

Tennis infrastructure in the old Yugoslavia was nearly nonexistent, and the many nights Djokovic spent huddled in a basement during air raids in the ’90s Balkan conflict were less than conducive to grooming a champion. At twelve Djokovic went to train in Munich under Boris Becker. Six years later, he was tearing through the rankings and making inroads with the press and public in New York.

Genčić’s golden child had the luck, or misfortune, to come to men’s tennis during the sport’s golden age. Of the freshman class making its dramatic entrance at that ’05 Open, Djokovic was the understudy. His teenage peers included Nadal, the Spanish star who entered as the second seed; Scotsman Andy Murray, who’d jolted the eternally squashed hopes of British tennis fans with a strong run at that summer’s Wimbledon; and the Czech Tomas Berdych, another Eastern European emerging just before the former Soviet Bloc ransacked the Open tour, befuddling fans and commentators alike with a deluge of unpronounceable surnames ending in -ova.

Djokovic had “not received the same buildup as his peer group,” wrote New York Times reporter Christopher Clarey at the time. But he had “the flowing baseline game, scary forehand and innate sense of geometry to make a major impact.” Astrophysics more than geometry describes Djokovic’s ascent: between 2003 and 2006, when he joined forces with coach and “family member” Marian Vajda, his world ranking leaped from No. 679 to No. 16. Federer lorded over the men’s game, with Nadal nipping at his heels and then becoming a formidable foe—from 2004 through 2007, all but three of twenty slams were won by either player.

There were many players vying to succeed Federer as king, but Djokovic was the only heir apparent who moonlighted as a court jester. Tennis had sorely lacked spontaneous personalities since the punk—or bratty, depending on your patience—days of John McEnroe, Jimmy Connors and commonplace on-court combustibility. Djokovic shied away from profane psychodrama, but injected humor into a sport, and a U.S. Open, that had become increasingly prim and corporate despite the burgeoning diversity of its premier players. At Arthur Ashe in 2007, Djokovic delighted the perennially excitable New York crowd by mimicking other star athletes. He sauntered along the baseline and flipped an imaginary lock of hair in a pantomime of Maria Sharapova, and incessantly picked at the seat of his shorts in a riff on Nadal, whose service point butt plucking had become a point of slightly embarrassed fascination among fans and television commentators. (Sharapova enjoyed the impersonation; Nadal, initially, did not.) “Unlike [Federer and Nadal],” Bob Simon said of Djokovic in a 60 Minutes profile earlier this year, “he seemed to be having fun.”

Djokovic toned down the rakishness once he became a legitimate contender for titles. His very serious game flummoxes opponents with a versatile combination of Federer’s finesse and Nadal’s raw power. The French Open has eluded him, but his talents translate across all surfaces. Although these days the top men make impossible returns seem the norm, Djokovic has an exceptional ability to lunge for shots that leave spectators in stunned silence as they sail over the net. The son of a pizza maker’s intensified focus extended to a macrobiotic diet and razor-thin physique in 2011 that had some members of the tennis elite murmuring that he’d gotten too skinny. (There were no publicly aired suspicions of non-organic genetic improvements.)

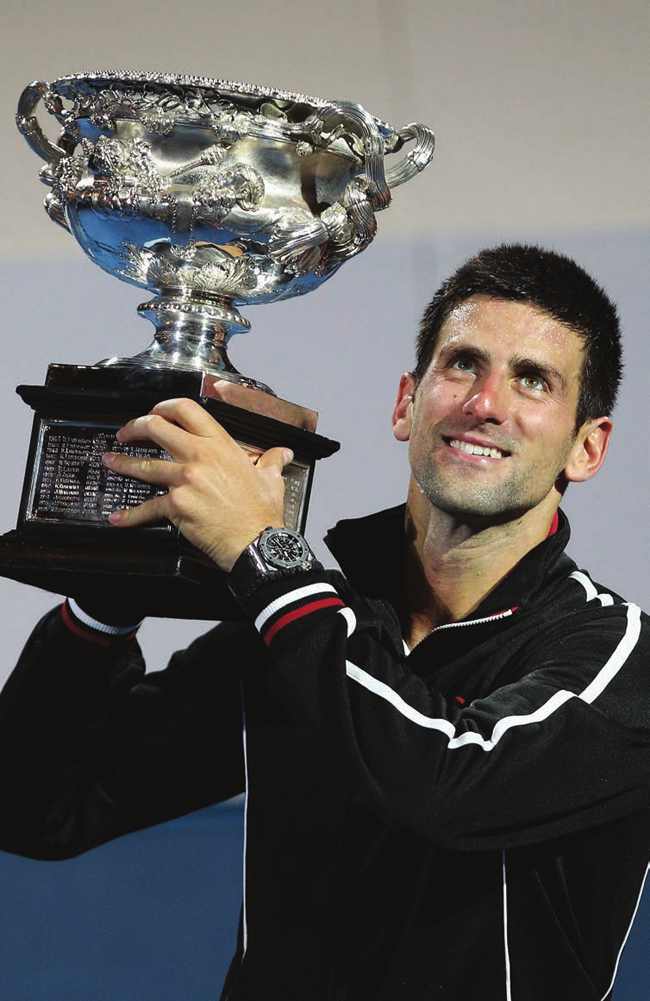

To the chagrin of simple carb-loving athletes, this nutritional discipline paid off. Last year Djokovic had one of the best tennis seasons of any player in the Open era. He started it with an Australian Open win, proceeded to take his first 43 consecutive matches and wound up winning all the Grand Slams save for the French. (Nadal, the preternatural artist on clay, took Roland Garros.)

Djokovic had realized two childhood dreams: winning Wimbledon and becoming the number one player in the world. Even with Federer, 31, on the wane and Nadal, 26, battling frequent injury, he wasn’t alone at the top. But he’d put his stamp on the men’s game’s golden age, altering its leadership structure from a duo to a troika.

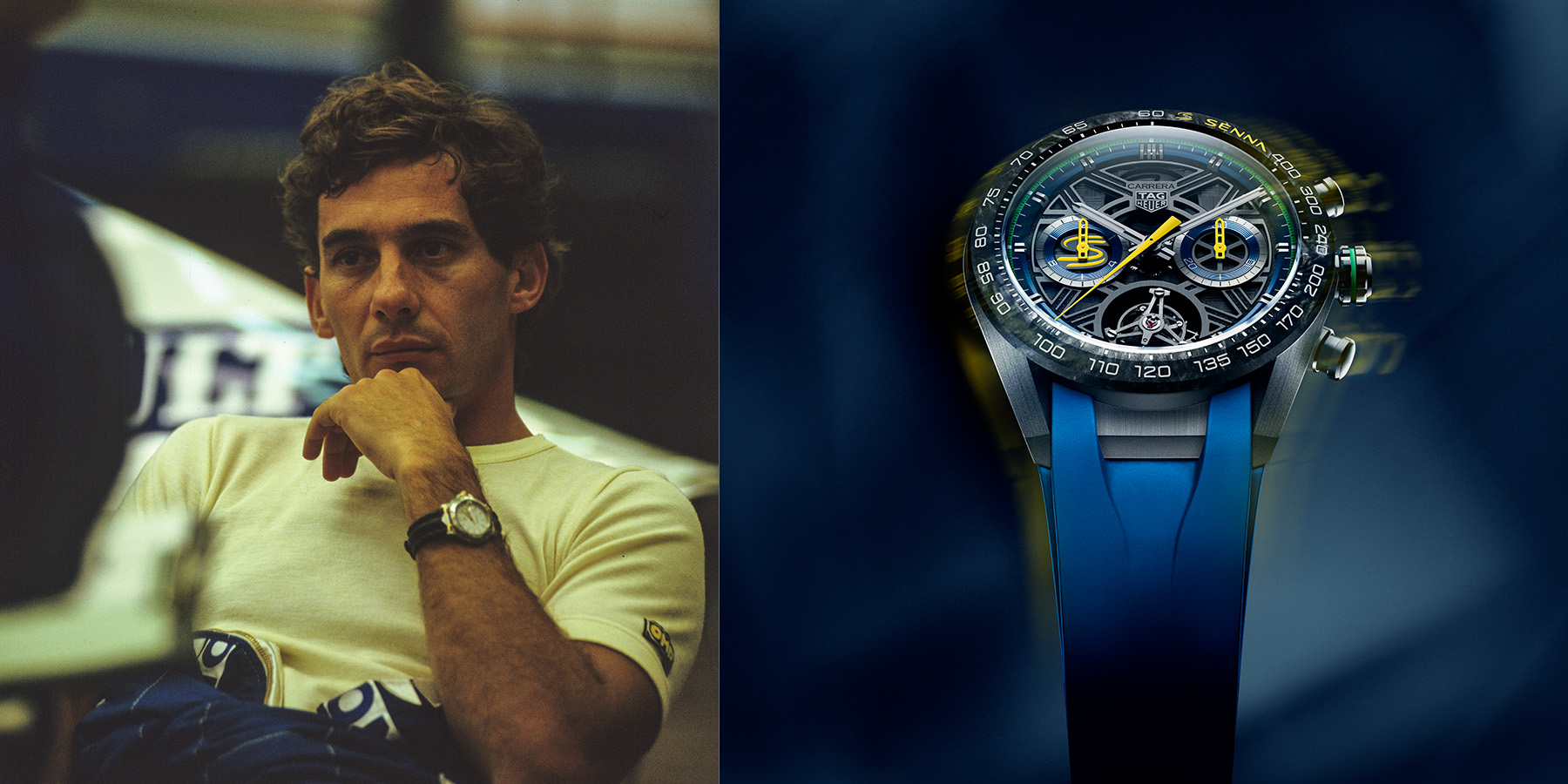

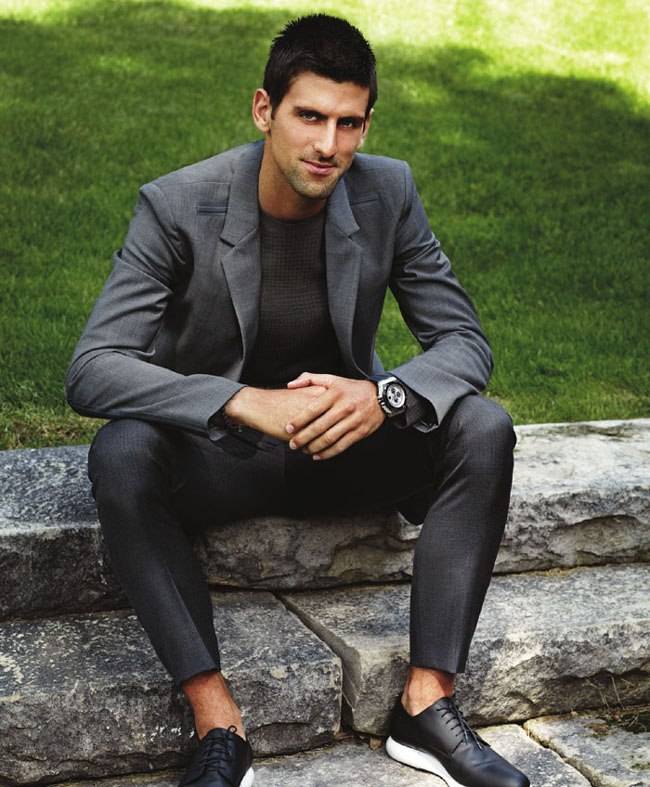

He was also becoming a star off the courts, filming a scene (that was later cut) for The Expendables 2. At the conclusion of the 2011 Open, iconic luxury watchmaker Audemars Piguet named him brand ambassador. Though an exquisite timepiece would hinder Djokovic on the court, he’s quick to wear one of the company’s Royal Oak models the moment play ceases. Djokovic told us he and the Swiss company share the same values: “We both break the rules by first mastering them.”

As for breaking records, Djokovic is hungry for more Slam wins in 2013. No matter how many future titles Djokovic has to split with however deep a roster of exceptional players, he’s assured icon status in Serbia. (Icon here can almost be taken in a literal sense—hanging in Srdjan’s office at the Belgrade restaurant Novak is a cherubic portrait of his son basking in the beatific glow of Patriarch Pavle, the deceased head of the Serbian Orthodox church.) He’s something of an unofficial Belgrade mascot, his amiable, impish face omnipresent throughout the resurgent city.

Djokovic is not content to just soak up the admiration. His eponymous foundation, which raised $1.4 million at a New York event two days after the U.S. Open ended, is committed to providing disadvantaged Serbian children with healthy food, solid education and, yes, the foundational tennis support Djokovic and his peers lacked. “Not many children from my generation had an opportunity to fulfill their dreams like I did, and many of them were discouraged from dreaming,” he told us. “I believe that every single person in this world has something valuable to give and share with somebody.”

SIGN UP

SIGN UP